It's a truly valid question and one that bakes my noodle as a graphic designer. It seems coders are more than ok with AI and LLM being able to produce workable and usable code in a number of programming languages. Traditional artists on the other hand have quite a different answer when that question rears its head, usually involving some venomous expletives. Lets not even venture into the realms of Quilbot and creative writers and their views.

Like it or not, AI powered tools are here to stay and you can either embrace them into your workflow with vigour or fall by the wayside in a puddle of your own salty tears chewing the ear off the person sat next to you in the pub about how technology stole your job and that it can come nowhere near to a real writer or artist.

Technolgy marches forward with or without those people but a very interesting thread by the awesome The Cultural Tutor came up on twitter posing an even more polarising question; Is AI art really art?

Is AI art really art?

— The Cultural Tutor (@culturaltutor) December 13, 2022

That's one of the biggest and most interesting questions of the 21st century.

And the answer might have something to do with this 500 year old drawing from the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci... pic.twitter.com/4XMGsPMWQD

Is AI art really art? That's one of the biggest and most interesting questions of the 21st century. And the answer might have something to do with this 500 year old drawing from the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci.

There's one sense in which AI-generated images are clearly art. They *look* like art and we are increasingly *using* them like art, so they must be. But that's not (usually) what people mean when they say AI can't produce real art. Perhaps there's something more to it.

Not everybody agrees on this, of course - AI art is exciting & challenging in equal measure. It wasn't long after the invention of photography - a challenge of no less significance to art than AI - that the French poet Charles Baudelaire wrote this:

Baudelaire's concerns are similar to modern fears about AI. And yet, two centuries later, we've had Monet, van Gogh, Picasso, Dali, and so on. Things will change, certainly. But there will still be art and there will still be artists. So maybe none of this really matters.

But, back to the question: is AI art *real* art? That depends, of course, how we define art. It's an incredibly broad and often useless term. Galleries are deceptive, for most art in history usually had a specific purpose and context. In any case, here's one possible answer.

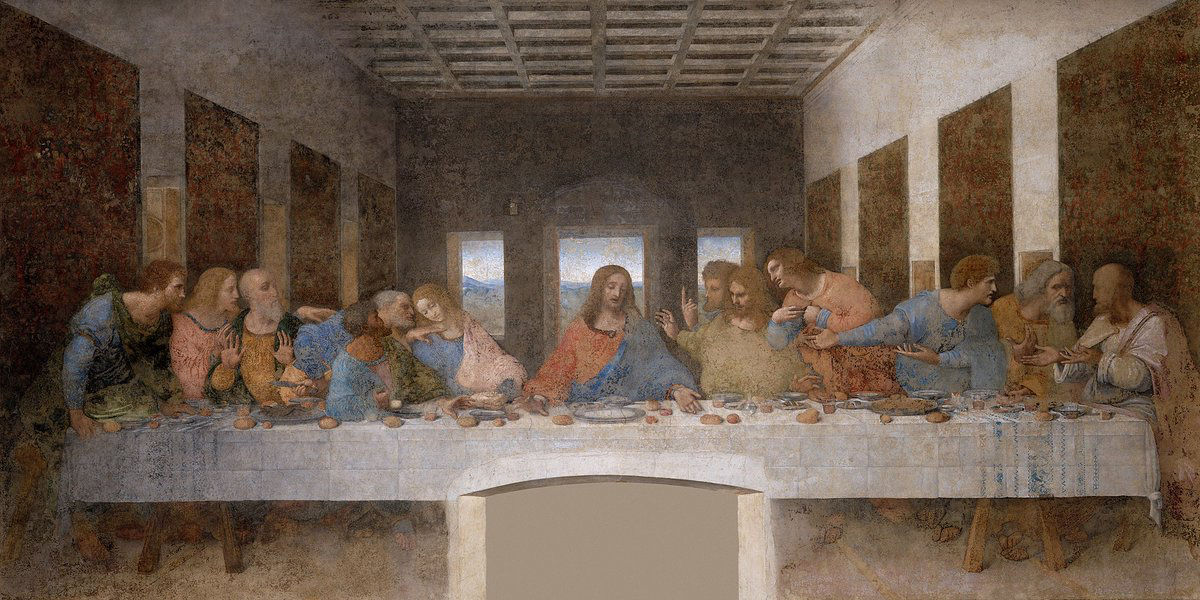

This sketch is from Leonardo's notebook in 1494. It's a preparatory drawing for the Last Supper, completed in 1498. He, like many artists do, was trying out different angles, poses, compositions, and expressions until he found the "right" way of depicting the scene.

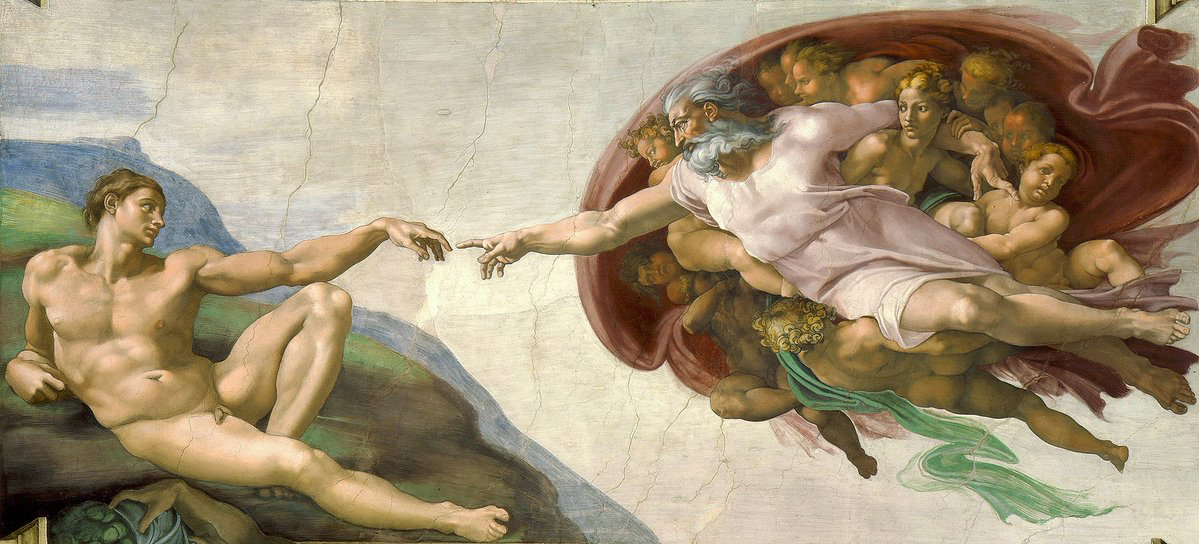

Renaissance artists were obsessed by composition, by the mathematical rules which governed proportion, space, and natural harmony. As you can see in one of Leonardo's preparatory sketches for an unfinished painting, the Adoration of the Magi, every single detail mattered to him.

Here are some preparatory sketches made by Raphael for his Madonna of the Meadows, painted in 1506. Notice the subtle differences between each sketch - minute alterations of pose and expression, of the precise relationship between each of the figures.

Why did artists make these sketches? Well, imagine if you decided to paint the Last Supper. How would you do it? The amount of things to decide are almost unquantifiable, from the precise pose of every person depicted to the colours of their clothes and everything in between.

This is about how and why an artist chooses to depict something *that particular way*, when they could have chosen from so many others. Whether subtly different, like Raphael's iterated sketches, or radically different, like the Last Suppers of Leonardo and Tintoretto:

There are essentially an infinite number of ways of depicting anything; every single detail can always be *slightly* different. It was this specific version that Leonardo chose to create. From an infinite number of possibilites, this was his personal vision of the Last Supper:

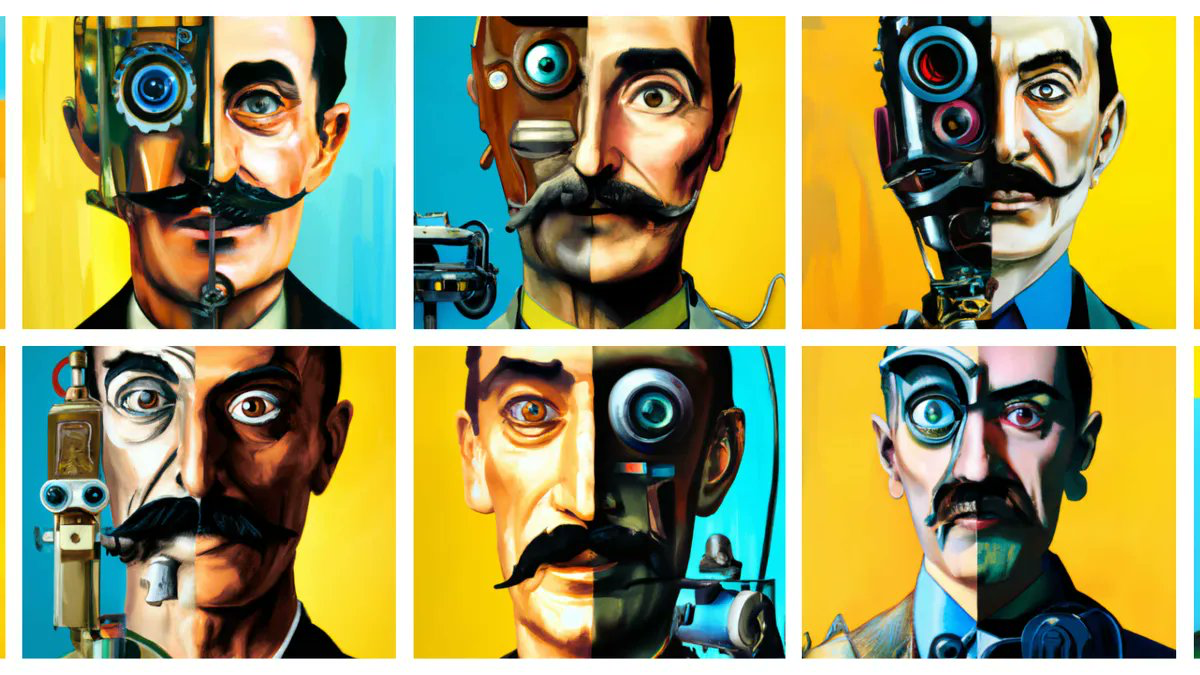

Hence why text-to-image AIs give multiple versions of prompts - the possibilities are infinite. The specific intention behind the details of much (but not all, of course) human art is absent from AI - it is only when people choose images that intention appears, ex post facto.

So this is the real question: when is a work of art finished? There's no objective standard. And so perhaps this is the "soul" of which Baudelaire spoke - the decision of an individual artist to depict something *that way*, and the congruent power to say that it is finished.

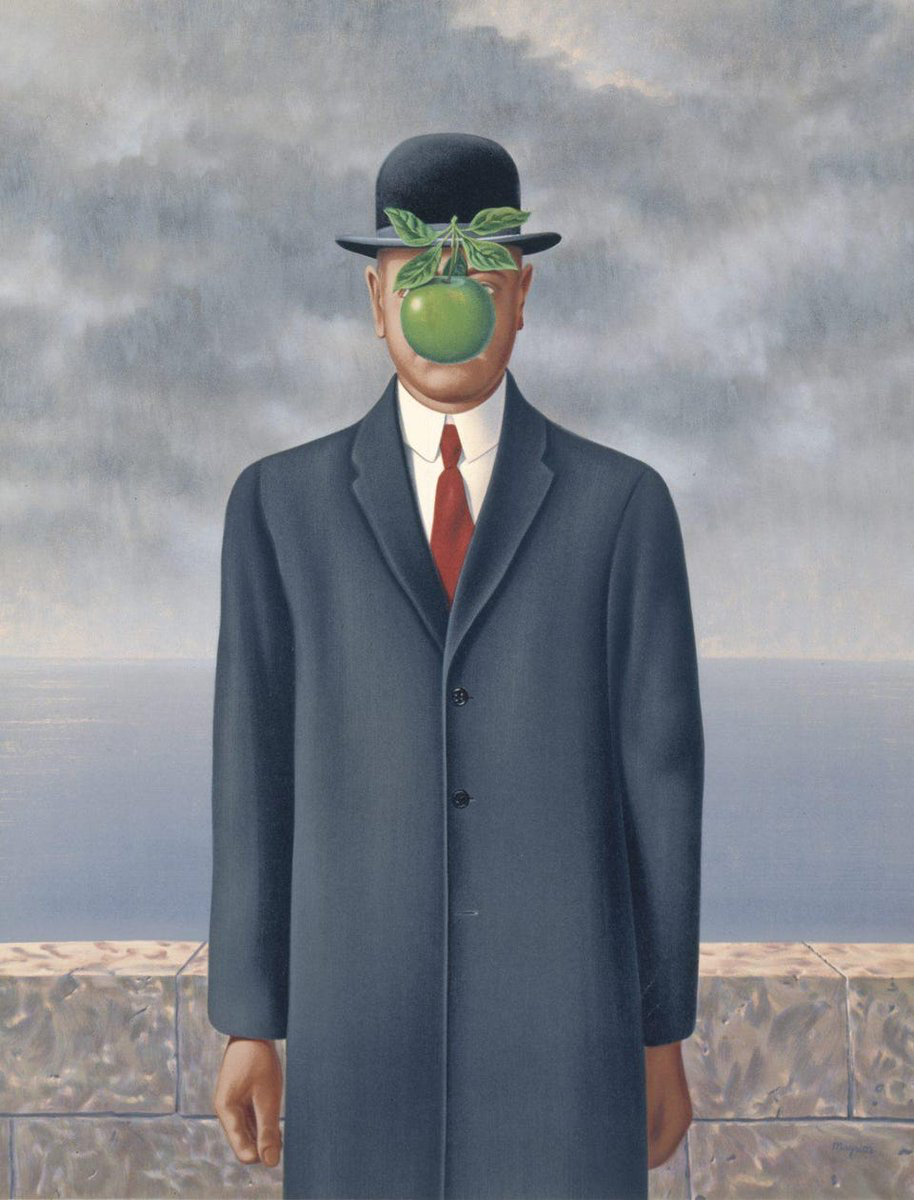

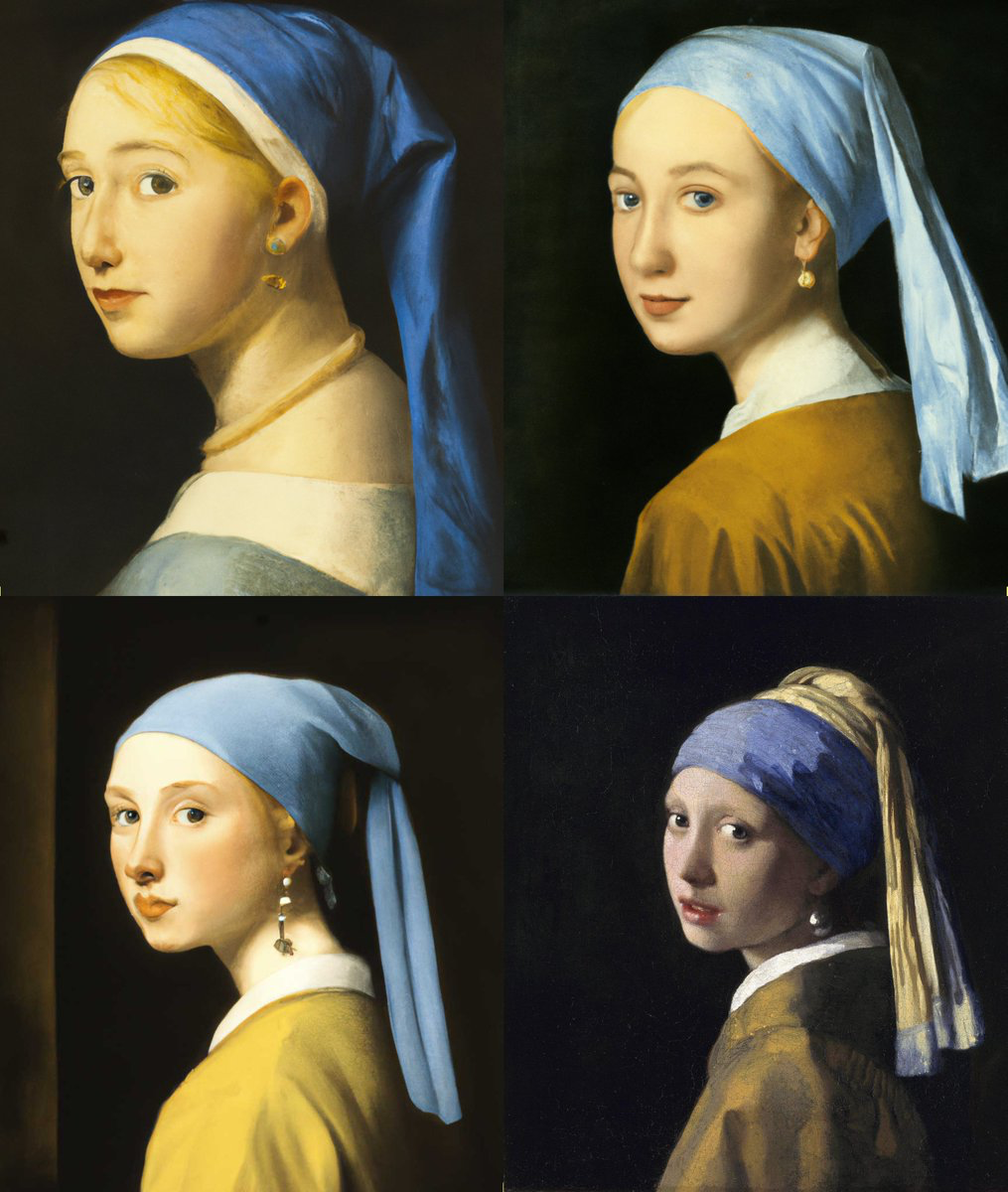

If we compare Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring to some AI-generated variations, can we say that the original is the best? You can probably make a case that it's objectively superior, for technical reasons or otherwise. It certainly seems the most expressive & captivating.

And here is Friedrich's Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog with AI variations. Again, the original seems to have an intangible quality which makes it "feel" better; such is the result of an artist's skill and intention. That being said, it is perfectly reasonable not to think so.

You might prefer the Vermeer and Friedrich originals, or you might prefer the AI variants. But taste is subjective - that's not the point here. What matters is that Vermeer and Friedrich, of all the infinite possibilites that lay before them, chose a specific way.

And this is something that, it seems, AI cannot (yet, at least...) replicate. It is in this grey area of subjectivity - of deciding precisely what the art should look like & when it is finished - where the strange creative process behind any work of art reveals itself.

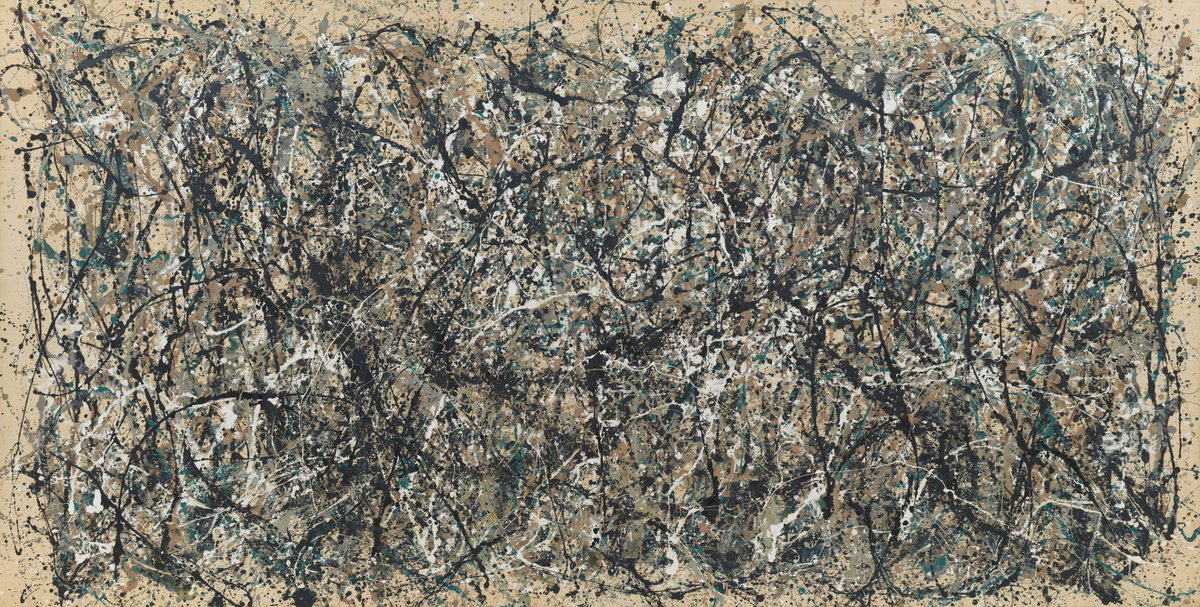

You might call this the feeling that a work of art is "just right", that nothing could be added or taken away, that it feels as if it was always supposed to be that way. A feeling encapsulated even in the seemingly random work of an artist like Jackson Pollock:

This applies to Leonardo or Vermeer no less than than to artists of every type today, whether in fine arts or cinema SFX or video games or graphic design. The ability of an individual to produce a highly intentional work of art, even working to order, is hard to replicate.

Of course, AI art poses an immense challenge to these artists - the careers of many will surely be affected. After all, it's cheaper and quicker to use AI than to pay somebody. So the question is really a technical one - whether AI can produce art of sufficient quality.

But, thinking of the examples from Leonardo and Raphael, there is a big difference between an AI-generated image and a deeply considered, personally-conceived work of art. Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night could not be by anybody or anything else, because it was he who painted it.

Perhaps there will be AI which achieves such individuality and sensibility; perhaps the technology will improve beyond belief. Some AI art has already been auctioned - Edmond de Belamy for $432,00 in 2018 was the first - and the cover of The Economist in June was created by AI.

Only time will tell the importance of AI art and to what extent it supplants humans - or to what extent they can work together. Can it replicate the soul shown by Leonardo when sketching out the Last Supper? Will people still recognise, admire, and pay for such soul? Who knows!

"Art" isn't what it was in Leonardo's time, nor even what it was a century ago, but art is still here, because it has been since the start of human civilisation. Like the printing press, photography, and the internet, AI is but another, exciting step in its endless evolution.

Related Posts

My AI Art this Week

Apr 07, 2023

#Diorama Tuesday

Dec 06, 2022

Super Babies. Eyes on Art

Dec 06, 2022